2019-02-28

Behind the Scenes of Data Inspector: Python, Rabbit and Other Animals

Hi, Olaf here. Being a part of the Marketplace team at Synerise (at that time), I was recently tasked with a certain job. I was supposed to create a kind of Proof of Concept for a new product that our team deemed to be useful for both our internal needs and the needs of our customers, improving the overall experience within the platform. This is how Data Inspector was born, or at least the idea behind it. This article will show you the actual workflow and its implementation. Also, take notice - this was originally posted on Synerise's blog!

If you are a beginner programmer, you might think that after receiving the task I just sat in my chair and started coding right away, quickly creating new code. At least that's what I'd think, when I had less experience than I have now - in my perception, programming was all about writing code and nothing else, just typing at your keyboard. Now I know how wrong I was. There's a great saying that accurately describes my former approach: "Quick, quick, before we realize this makes no sense". I often did that in the past - code first, think later. It's the wrong approach in most cases that in the long run leads to a disaster.

Anyway, the first thing I had to do, after starting to work on the project, was to just… think. Think about a lot of things. Possible use cases, user needs, the future and how to create something that will be manageable, easy to develop later if it turns into a full-fledged product and so on. Trust me, that's not easy, especially if you are just a junior developer like me. Let me give you a brief overview on my thinking process, research and what I've come up with.

Some assumptions

After getting a clue about what this particular product should do and what problems it has to solve, I had to translate these business requirements into technical requirements. I was almost completely free to make any choices I wanted. Freedom is great, but the abundance of choice it brings can also be a curse. Be careful not to fall into this trap - it's better to choose anything than to be indecisive.

After talking with our Marketplace's PO, a UX/UI designer, and further consideration about the nature of this project, I came up with a couple of key points regarding the architecture of the product I had to create:

1. It's asynchronous in nature

Data Inspector lets you - can you guess? - inspect data. And the amount of data we receive can be seriously big. Gigantic. Enormous. If you work at Synerise, then more often than not, it won't be a matter of 'can be' but of 'is'. This makes things a bit more challenging and fun, because you can't allow yourself to be sloppy with some things, as in the case of when the data is small. One of the things you have to think through is how your user interacts with the application while it's doing its thing. What do I mean?

Usually when you do something in a web application, you either see the results immediately or after a couple of seconds of looking at a spinning circle. The problem arises when it takes long to process the action you triggered - your request, in other words.

What if you had to wait, say, twelve hours with your browser and a given tab open in order to obtain some result? Now also imagine that closing that tab/browser/losing your internet connection would result in a failure and you had to do it all again. Is that a viable flow? Of course not. That's where asynchronous thinking comes in. Usually, when you work with code, it's executed synchronously - one line after another. The second line won't start executing until the first one has finished. That wasn't a viable choice for what we needed.

Asynchronous programming enables us to solve this problem. Instead of waiting for a particular piece of code/method/function to finish, we just tell the computer to carry on with executing the rest of the code. That's a very simplified approach but you can think about it in such terms.

Basically, that's what I wanted - to improve the entire UX. Instead of making them wait with a browser/tab still open and loading for hours while we do our number crunching, let's tell them that the request was scheduled to be done and it will be at some time in the future, and we'll notify them by, for example, sending an email or continuously streaming the results. Much better, right? This kind of illustrates what the asynchronous nature of the project allows us to do.

2. Easily scalable & containerized

At Synerise, we heavily use Docker and Kubernetes and all the features they bring to the table. Considering this, and the fact that it's just convenient, the need to use containerization was obvious. It would also enable us to scale the app easier in the future, when, for example, our app receives A LOT of traffic or serves loads of daily users.

But what is containerization? In plain terms, it just means packing everything your application needs into something called a container in which your app will run. It needs nothing else, just the things it has in the container. This often means that deploying or running your app locally requires you to type one line in CLI.

That's neat compared to the old way of having to install things by hand, then trying to match given versions of dependencies and manage all that mess. Containers, on the other hand? Neat and clean. Speaking of neat…

3. Designed with micro-services in mind

While I'm not an absolute fan of micro-services and using them everywhere, they have their advantages. They're easier to scale, maintain and have other advantages. I like that - the approach where you create a lot of very small pieces of code, functionalities that do just one or a few things. But they do it well and that's all.

It's a joy to maintain code like that, with short, readable and descriptive methods. Logic that is clearly defined and easily understandable. A dream indeed, or at least it was a dream for me and Tomasz - another developer who's a part of the Marketplace team and who helped me with this project.

It's hard to implement such a thing, but I decided to at least try to keep this goal at the back of my mind.

These are the three main ideas and goals I had in mind when working on DI.

Architecture - let's get down to the details REST API

Considering how it would be a web application with some kind of user interface, and also not a monolith, one thing was sure - we needed an API, preferably a RESTful one. I could have gone for GraphQL or gRPC but… Honestly in this case, where two or three endpoints was all I needed, it would be just a waste of time. Let's stick with simple REST API here.

And when it comes to developing REST APIs, the choice was simple, but let me walk you through it.

My language of choice for this project was Python.

While I had some experience with other languages, I'm at my best with Python. Python is also a good choice when you want to develop MVP because of its powerful conciseness and expressivity - a small amount of code can create wonders, a lot of packages are freely available and so on. It's also fast enough, readable and just beautiful. I love Python, my feelings aside though, it's a perfect fit here.

Writing everything on my own from scratch would be a huge waste of time, so I decided to use some kind of web framework to help me in my work. My choice fell between Django and Flask - two widely used Python web frameworks.

While I like Flask's micro- approach, I've found that in this particular case, setting up everything that Django provides out of the box, in Flask, would consume a lot of time while not providing any visible benefits. Another point for Django: it has a very powerful and robust framework created for writing REST APIs - Django Rest Framework. It just was the best fit here. The next advantage of Django is that I already knew this framework and had worked with it previously, so I wouldn't have to learn everything from scratch. I also had a lot of people around me who knew Django & Python really well and could help me in case I got stuck. That's really important in picking you stack. I remember once working on a project written in Dart. While the language itself is really cool, lack of community makes it a nightmare to develop a project written in it.

Asynchronous stuff

More often than not, when it comes to asynchronous code in web apps written in Python, a standard solution would be to use Celery, coupled with some kind of broker, probably Rabbit or Redis. What is all that?

Broker, task, queue, worker. Well, a task is just something you want to get done. Worker is, let's say, a piece of something that will "do" the task, spend resources on it. Queue is a place where the tasks are put and continuously taken by one or more workers, often in a particular order. As for the broker it's just something that, let's say, puts the task in a queue and communicates with your workers, making sure all things go smoothly.

This is a very simplified description, but just in case you are not that familiar with these terms, you might think about them as described here.

So, usually, what I'd do is use Celery+Rabbit to do my asynchronous tasks. It's just the standard. This time I was going to do the same, but Kacper, our team's leader, recently made us think a bit in the context of another project.

If you setup Celery+Rabbit/Redis, you have two more things to care of, two more things to monitor, update and so on. But it so happens that a certain piece of our functionality is heavily tied to something called Kafka. It's a kind of broker, but more.

Because of how our business depends on this thing working, our Ops team has it under control 24/7, they take a really good care of it. This means two things.

First off, we can substitute two pieces of our puzzle, Celery+Rabbit/Redis, with one - Kafka. Less code and fewer pieces of software, less stuff that can go wrong. The best code is the one that doesn't exist - it has no bugs whatsoever and takes no time to maintain. Second - it takes managing, monitoring and maintaining the Celery+Rabbit/Redis cluster off of our heads.

Kafka is already managed by the Ops team. Besides, connecting another app to the Kafka cluster wouldn't add any work to their plate, but it would take a lot off from ours - the Ops team will obviously be better at maintaining a cluster than we would be.

This Kafka is taken care of like a king - unlike a Celery+Rabbit pod, which wouldn't be so critical to the whole company, like Kafka is, but just to some particular project. In plain terms, switching to Kafka would enable us to do the same thing with less work.

What are Kafka's other advantages?

Well, in short, it's fast, like really fast. We need that - as at Synerise we process A LOT of data. It's fault tolerant as well. It's horizontally scalable, meaning that if things are going slow, just throw in more machines, which is often a better approach than scaling vertically and adding more hardware resources to one server. The idea behind it is very simple and easy to grasp. It works like a messaging system and has a persistent log storage. The last one is very important. I could write about Kafka all day here, but it's not the point.

What is important is the fact that it fits really well into our other project, so the decision was made to switch to it.

Now I wouldn't have to deal with Celery, Rabbit and unnecessary stuff. Plus it's better to rather unify things rather than to have each developer/project/team work in different environments when you can easily have one. I used Kafka as a broker, coupled with a simple consumer and producer. A few lines of code and bam, it works. But before all of that happened, a dilemma appeared. Kafka has two libs in Python: PyKafka and Kafka-Python. Both look stable, mature and popular. Both do pretty much the same things. Now a question arises - which library to use?

Was this another pointless tangent of some project doing the same thing but in a different way? How long would we have to think and decide? Well, as it turns out, it wasn't that hard. First off, PyKafka had, subjectively speaking, better API - it just felt nicer to interact with, but what was really important was that PyKafka can use, a kind-of-a extensions/header, that instead of being written in Python, which is just fast enough, was written in C, and runs with C-level speed. So… Goodbye Python-Kafka, PyKafka is my friend now.

Database

Now, there's a need to store stuff for our application. Where? A database of course. After some pondering and modeling, I came up with a proposed model where data would be rather relational in nature. I found no point in trying out NoSQL solutions or any kind of document-based database.

Instead, I decided to stick with plain old (but still amazing) Postgres. Also, it would be managed for me by our Ops team as we already have plenty of instances of PG running. That's it, then - no reason not to use it. It performs well enough, and fits in the designs and functionalities.

Storage

Considering how DI needs to work on data, I needed a way to persistently store it somewhere for a period that would allow us to do the processing. Imagine what a pain it would be to upload the same file when you want to run some tasks on it again. What a nightmare. It should be enough to upload it once - then you should be able to run an arbitrary number of tasks on the same file.

Technically we could do that with a DB, but it wouldn't be my first choice. Do you think that using DB to store very large files is efficient, cheap and good? Well, in this case, not really. I decided not to use a database. Considering how we want our storage to be persistent, we can't just load the file in memory. Besides, have you ever tried reading a 200 GB file in memory? Now imagine you have five clients like that doing it simultaneously. How about a hundred clients? Good luck with that. Let's just say it wouldn't be a good idea. So… some kind of storage it is, but what, exactly?

The choice is simple. At Synerise, we use Microsoft Azure. This enables us to deal with files of almost unlimited size. Why?

Well, imagine someone decides to run a task on a 200 GB file. Been there, done that. How about 2 TB? Been there, done that. Now, if we just stored this locally, it would mean that our cluster instance would have to have a disk that contained all of that data. The cost would be high and efficiency would be low. It just isn't a viable solution.

Storage though, changes all of that. First off - we don't have to worry about any infrastructure or file/disk maintenance. Another thing is that we can simply stream a user's upload directly to Azure and there's no need to have it on our pod.

Lastly, inspection of a file like that will provide persistence and also allow us to stream and inspect user data chunk by chunk. This means that we can pick an arbitrary size of a chunk that we download from storage. Let's say it's be something small enough to fit into memory, and process just that - without writing anything to disk. Neat, right?

But wait. DI is mostly designed to work with user files that the app pulls from SFTP/AWS/FTP, from somewhere. Couldn't you just download it every time and forget storage? Honestly, no. Let's start off with the fact that the processing might take a while - during that time a given file would have to be available continuously on client's server/source. This might sometimes get tricky. What if a client decided to change the file in the middle of the process?

When downloading a file though, just piping two requests doesn't take that much time. Downloading a file will be a lot faster than doing complicated processing on it. So in case we download the file to the storage, our user has to make sure that the file is available on a working server for, let's say, X amount of time - just the time it takes do upload it to storage.

If we just continuously process chunks downloaded from the client's sftp/api/whatever instead of storing it in Azure Storage, that time would reach, for the sake of argument, 10X. This is the wrong approach.

Another point: it costs a lot. Downloading the file, outbound network that goes outside of Azure - this costs money. Traffic that moves inside of one Azure DC for example, is free. A lot of money can be saved this way, believe me.

Conclusion regarding the architecture

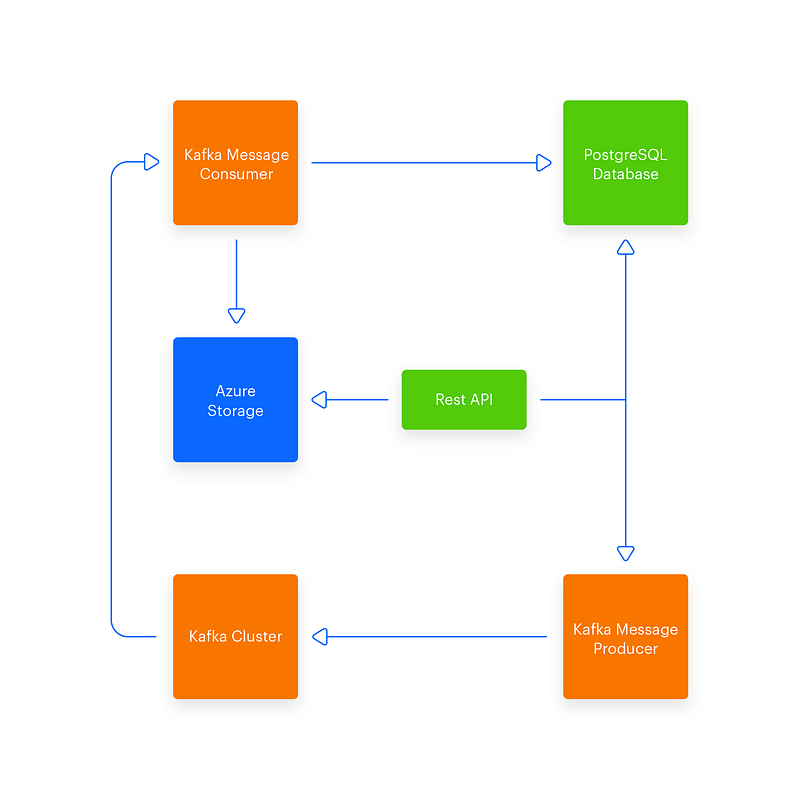

So in the end, this is what I came up with: Django+DRF, Kafka wrapped in PyKafka, PostgreSQL, Azure Storage. Containerized apps. That's all. Simple, huh? Good, that's how it should be. This is what it will look like:

That's all when it comes to the initial architecture I'd like to implement. While it may look fairly simple, this took a long time to properly visualize in my head and become clear. Do you think it's time to start coding? Not yet.

Workflow

Other than thinking about architecture, before you actually start a project, you should at least define an outline of the workflow you'll use during development. The one I propose here, among many things, is something I’ve learned from my friend and mentor – Sebastian Opałczyński. Many kudos to him for teaching me so much and just genuinely being a good human.

Let's start with a VCS I'll use. If you ever encounter a company where instead of using VCS, Git preferably, they use versioning code via archives or excel sheets (don't ask…) then just run. As far as you can. For this project I started with Git + BitBucket.

Considering how small the code base will probably be in the future and the fact that's just an MVP really, I decided to run with mono repo - one repository for all the code, but while writing it, I tried to keep in mind the fact that in the future I might want to split it to even smaller pieces.

Branching

In the repository, I'll use two long living branches: master and develop. Master will be the branch that represents the production (which we won't have in the near future) state. Develop will represent the development environment.

Each feature/bug/fix/whatever will be created in a separate branch. Branch names cannot be random, so some standardization must be introduced so that you may keep order. For me the format specified below works quite well:

Branch name: <kind>/<task-reference-number>

Meaning marks the type of change you make: is it a new feature? A bug? Hot fix? Task reference number only applies if you use task tracing software that assigns numbers by itself. In our case, it's Jira and Atlassian stack.

For example, this is how a branch name might look like feature/DI-001, bug/DI-123 and so on. If you don't use any kind of task tracking tool, just stick with <kind>/<2–3 word description> or even just <2–3 word description>

As for the commit massages, I think they should contain branch name, eg:

[feature/DI-001] commit message

Each branch should result in a pull request, which has to be reviewed and approved by at least one person other than myself, preferably more.

If the PR is not approved, it cannot be merged.

Pipelines

I've learned to heavily use pipelines in my project to automate some stuff, to ensure that the code doesn't get worse with each commit and doesn't get messier.

In my pipelines I run tests, build docker images, push to docker registry and even deploy things. Every branch is run through tests and some interesting tools.

I've decided to use: Isort, a tool that checks the ordering of our imports. It makes sure, that later, when we can have a lot of import in one file, they're still manageable, ordered and neat. Flake8, which checks your code against pep8. Bandit checks your code against potential security threats.

If any of the above tools produces an error, the pipeline fails. Some might say this is an overkill, this will be annoying and all. Believe me, no. If these rules aren't enforced, sooner or later your code will look messier than it should or could have. YAPF - Yet Another Python Formatter. The very name makes me like it. There are cases when one developer might argue with another about whose style is better, more readable and so on. To hell with that. Let's just make in automatic - YAPF automatically formats the code according to the rules defined in repo's settings. No more argues or pep8-ing your code in PRs by others.

This, in turn, doesn't cause the pipeline to fail - YAPF just formats the code and that's it. First, the pipeline goes through code checks, then runs tests - that's the default step for every branch. For develop, I've set up two extra steps: bumping the current version and then building, tagging and pushing docker image to container registry auto deployment of the new version

As for the master branch - only bumping and pushing, no auto deployment.

Why? Well… Got no production for now, but in new, volatile apps that change constantly, as MVPs often do, auto deployment on production might not be a good idea, so let's be careful with that. And why do I use bumpversion? Well, versioning the app is a must and if so - why should I do it by hand, if it can be done for me? Automate what you can. Why versioning is a must? Well, after some time your application will have lots of versions. Like really a lot. You want to know which version runs where, on what environment. If an error occurs - same thing, on which version it did, since what version do we have it. Also, it makes managing your container image registry easier, more readable. Usually apps versions have three parts: major.minor.patch - eg 1.3.41 When I merge PR of any branch to develop, I bump the patch part. If develop to master, then minor. If there are some reaaaly big changes that break everything, then I go for a major version bump.

I hope you enjoyed my scribblings so far! In the next part we'll talk about the codebase and stuff.